Related Articles

- What is the efficient market hypothesis?

- A lesson from the stock market

- The Warren Buffet problem

- The problem with finding an edge

What is the efficient market hypothesis?

The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) is an economic theory asserting that the information within a market is fully reflected by asset prices. This ensures that creating abnormal profits consistently through skill, otherwise known as beating the market, is impossible.

A lesson from the stock market

When talking about market efficiency the stock market is perhaps the most relevant place to look. The efficient market hypothesis has been much discussed and studied and there is evidence that is relevant to betting.

However, unlike long term stock trading, sports betting is a negative-sum game. That is to say that the total of the gains minus losses in the market is negative due to the bookmaker’s margin. To even maintain the status quo (breakeven) a bettor must take from another participant.

This is very different from general stock market investing where it is possible for all to win (and the market has historically risen).

However there are actors within the stock market which behave not too dissimilarly to bettors, namely active investors.

Hedge fund managers in particular attempt to provide value to their clients by beating the market. The fees paid to such managers act almost like a bookmaker’s margin. Investors are forgoing standard returns and paying fees to see abnormal profits.

However, in a benchmark study economists French and Farma found that only the top two to three percent of hedge fund managers had demonstrated enough skill to even cover their costs when compared to general market growth. The rest could not even do that.

As Farma says “we don’t understand the negative-sum nature of active investing. Whatever you win, I lose. Whatever I win, you lose, and we both paid to play that game”.

With the constraint of working against margins (in this case their own fees) the number of hedge fund managers that actually beat the market due to skill was minimal and diminished over longer time periods. These are people paid for their investment expertise.

The Warren Buffet problem: Profiting in an efficient market

So the evidence suggests that in a truly efficient market, beating the odds is impossible. However, one high profile investor bucks the trend: Warren Buffet.

Since 1965, the S&P 500 has delivered annualized returns averaging 9.7% (including dividends). Over the same length of time Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway has generated an average stock price gain of 20.8% per year, or slightly more than double that of the S&P 500.

So if the stock market is really efficient, how is it that Buffet has managed to return better than double market growth year after year?

One answer is that he has simply been incredibly lucky. There may be a chance that Buffet’s position as a mythical investor is just an extreme example of survivorship bias.

Whilst it seems unlikely, an investor could match Buffet’s returns (thinknewfound find a 0.07% probability a random investor could achieve a result as good as Buffet’s or better) it’s possible.

However, here we are interested primarily in Buffet’s ability to beat the market at all, which given his track record and the low probability an individual investor could match his returns it’s highly likely he can. “The magnitude by which (Buffet’s) Berkshire beats the market (an average of 12.24% annually) makes “luck” an unlikely explanation.”

This is interesting since, if Buffet’s success is down to skill, in a truly efficient market an investor like him should not exist.

Is the betting market efficient?

Pinnacle’s closing line odds are efficient but it can be argued that odds take a “random walk” towards the efficiency of the closing line.

Promisingly for bettors most interpretations of EMH do not claim that stock prices are correct at all times, only that prices are correct on average. The fact that sports betting hedge funds exist demonstrates that there are inefficiencies to be exploited in the betting market.

Unlike their stockbroking counterparts, if these firms are not performing they will actually be losing their (very wealthy) clients’ money rather than coasting on “profits” driven by a growing stock market.

In order to turn a profit these funds are likely to be beating the closing lineconsistently, suggesting there is room for an edge to be found between opening and closing prices.

Is there hope for the average bettor? Finding an edge

In order to profit in a market as efficient as sports betting, a bettor likely needs to be in possession of superior information compared the rest of the market or have a better interpretation of widely available information.

The problem for a smaller bettor is that when betting on a highly liquid game they are up against the parties with a wealth of information. The market is often shaped by those who know the most through reverse line movement, making things difficult for the average bettor.

However, this does not mean the average bettor should be put off from attempting to create his own long term profitable edge. Warren Buffett himself claims to have benefitted from competing against “opponents who have been taught that thinking is a waste of energy”. There are opportunities for those who seek them out.

- Read: Asymmetric information

Example of a potentially profitable bet: Mo Salah and expected goals

Below is an example of my actual reasoning behind placing a number of outright bets on Liverpool new signing Mohamed Salah ahead of the 2017/18 season.

Salah arrived in England without much fanfare, having not exactly set the world alight in a brief spell at Chelsea.

Perhaps this was why some bookmakers were willing to offer 13.00 on him to score 15 premier league goals in a season, matching the number he scored in an AFCON interrupted year at Roma, whilst Pinnacle were offering 51.00 on him to top score in the Premier League

This was a possible opportunity for bettors who knew how to use widely available information to their advantage.

Expected goals were less prominently used at the time and provided a really handy metric for determining whether betting on the Egyptian offered value. They provide a larger sample size to work with than actual goals scored and raw data is less prone to the lazy judgement bestowed on Salah after his earlier Premier League struggles at Chelsea.

Here are Salah’s xG (expected goals) outputs for his previous two seasons at Roma (scoring 15 and 14 actual goals in these seasons):

These numbers are impressive, especially when considering Salah previously demonstrated finishing skill that shows there was around an 80% likelihood he was an above average finisher. He has outscored expected goals in every full season he has played.

These raw stats show that as part of Roma’s team Salah was very likely to score more than 15 goals as long as he played around 30 full 90 minute games.

Based on his stats in Serie A this bet offered huge value. This would have to translate to the Premier League though so it was important to look at his new role within the Liverpool side.

At Roma Salah nominally played on the right wing but in reality often took up more of a striker’s position on the right hand size of the penalty area. The Roma team was primarily focused around getting chances to Serie A top goal scorer Edin Dzeko.

The Bosnian offered some assist potential (0.16 expected assists per 90) but was primarily a goal threat (0.96 xg/90, 5.25 shots per 90).

As a result Salah became a great assist provider for Dzeko. Salah created 22 chances for Džeko in 2016/17 of which seven became assists; only Ousmane Dembélé to Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang was a more lucrative connection with ten.

As well as offering goalscoring threat, Salah would often sacrifice his own shooting opportunities to provide for the Bosnian striker.

In contrast, at Liverpool Salah would be playing with the more creative Roberto Firmino (0.23 expected assists per 90 and 2.92 shots per 90 in 2016/17).

Preseason was a good indicator of what this would mean for the Egyptian. His role was similar to the one he had at Roma but with more emphasis on finding the back of the net, with Firmino more involved in general build up play. He was the most advanced Liverpool player, entrusted with finishing off opportunities that he may otherwise have passed on to Dzeko.

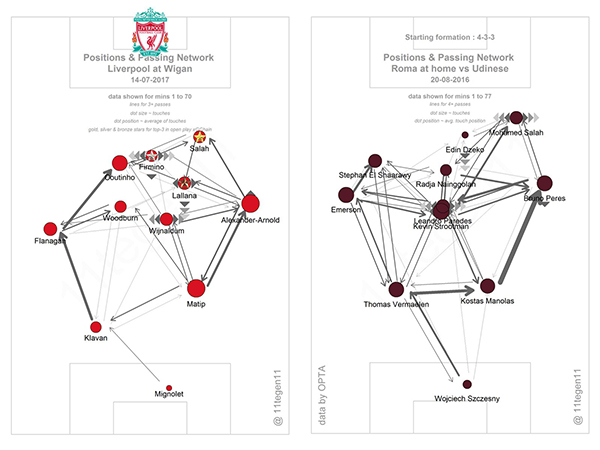

This was evident from preseason pass network data available from @11tegen11. Firmino’s larger marker demonstrates his greater overall involvement compared to Dzeko whilst Salah is starting to receive the ball in more central locations.

This role looked to be hugely promising for Salah and I anticipated a steep rise in his expected goals as a result. This was borne out in practice as Salah’s numbers proved to be exceptional (0.77 xg/90).

The problem with finding an edge

Information gets distributed quickly. Finding a player as unfancied as Salah with the same underlying metrics would undoubtedly be a harder task now.

Equally, it’s actually a big advantage not to be playing with large sums of money on these kinds of bets. They are attractive because low liquidity means inefficiency, however as bankrolls grow the relative returns diminish (especially as you will be limited by some bookmakers)

The other problem is the scarcity of these types of bets. Whilst Salah may have been mispriced he could easily have picked up an injury or been outscored by someone else having a great season. It’s not a repeatable bet, so the advantage can’t even out over time as it could with a successful model which works on an individual game basis.

Conclusion

Whilst Pinnacle’s closing line odds are efficient for high volume events, there will always be opportunities for enterprising bettors with the skill and determination to find and exploit inefficiencies in the market. Taking advantage of such opportunities can become problematic, however this is not a bad problem to have.