Related Articles

- Finding value in a bubble

- The necessity of shorting for market efficiency

- The importance of two-way information

What is a bubble?

A bubble occurs when an asset is valued in excess of its intrinsic value. In betting terms the intrinsic value of a bet is the true probability of the event occurring.

When placing a value bet a bettor is looking for an event where the “intrinsic value” probability of the event occurring is more likely than that implied by the odds.

Finding value in a bubble: Subprime mortgages

Michael Lewis’ “The Big Short” tells the story behind the US Subprime Mortgage Crisis focusing on the few who saw the crash coming and managed to short, or bet against, the housing market.

According to Lewis there were only around 20 parties in the World to do so. One such firm was investment firm Cornwall Capital.

“Cornwall seeks highly asymmetric investments, in which the upside potential significantly exceeds the downside risk. The firm has produced an average annual compounded net return of 40 percent (52 percent gross).”

Cornwall Capital’s Jamie Mai outlines their approach to trading as seeking situations where they had “conviction that the odds were substantially mispriced, providing us positive expected value”.

The necessity of shorting for market efficiency

So why were Cornwall one of the only parties to bet against a clear bubble with such high expected returns available? After all, Pinnacle’s odds show us how efficient betting markets are (and shorting is just a variant of betting). Surely the market should have corrected itself?

The issue here was the inaccessibility of the shorting option. Unlike a betting market, where staking is easily accessible to all parties, betting against the housing market was convoluted.

In essence, those optimistic about the housing market could easily bet on a continued rise by buying houses or mortgage debt bonds. The only easily accessible option for those wishing to bet against the market was simply to sell housing (although even sceptics need a place to live) and not buy bonds.

The Bitcoin bubble is another such example where the market price was set by optimists, causing over-valuation and an eventual crash. Optimists could buy Bitcoin whereas, at least initially, the only option for sceptics was to not hold Bitcoin themselves.

Interestingly, in a sports betting context we are looking for the opposite: the price to be set by the most pessimistic seller. The price needs to be “wrong” without the liquidity to correct it.

In this interview with datacamp Pinnacle’s head of trading Marco Blume talks about using Pinnacle’s customers as an “army of consultants” who can predict outcomes better than Pinnacle’s traders:

With such a sharp clientele setting the lines how could a betting “bubble” ever exist?

Have we ever seen a sports betting bubble? Mayweather vs. McGregor

Whilst the betting market is usually rational there is perhaps evidence of some very rare bubble-like behaviour. The clearest example of this that comes to mind is the Mayweather vs. McGregor boxing match.

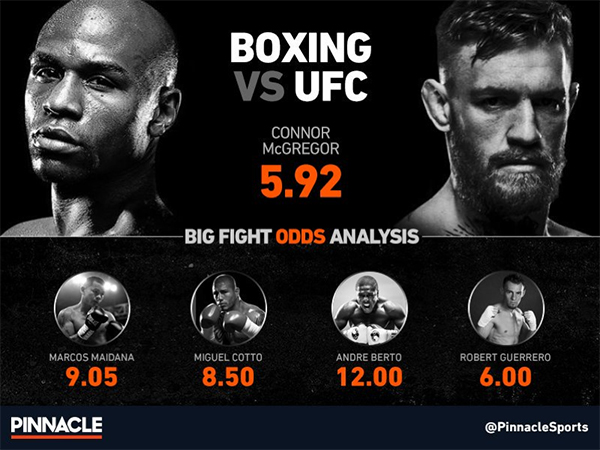

Take a look at this graphic posted to the Pinnacle twitter account prior to the fight:

Recent Mayweather opponents

Pinnacle’s odds on the morning of the fight implied Mayweather (1.196) had an 83.6% chance of winning the bout. In contrast, he was as low as 1.02 with some bookmakers, or a 98% implied probability, to beat WBA interim welterweight title holder Berto prior to that fight.

In fact according to probabilities implied by betting odds, of Mayweather’s opponents since 2010, only Manny Paquiao and Canelo Alvarez had a better chance of beating Mayweather than the untested McGregor, and even Alvarez only narrowly so.

Favourite-longshot bias does not adequately explain this behaviour since Mayweather offered what looked to be a clear value bet, yet sharp customers still did not come close to correcting the market (Mayweather’s true odds to win the fight should proabably have been in the region of 1.01).

Arguably the entire bookmaker margin and more was placed on the side of the Irishman, allowing Mayweather to offer strongly positive expected value bet.

Perhaps the barrier here was the sheer volume of money needed to counteract the payout on such a highly backed outsider. Value bettors simply could not wager the volume required to correct the inefficiency.

This was truly a market dominated by the most optimistic buyer. Ordinarily the sharper price-sensitive customer would have gone some way to correct this but, not unlike the housing and Bitcoin bubbles, the Mayweather backers were easily outweighed by optimistic McGregor bettors.

What lessons can be learned from the two sides of market efficiency?

When markets don’t have equal flows of information represented by money staked, they can get out of sync and inefficiencies appear.

Mayweather vs. Mcgregor style inefficiencies, where over-optimistic backers distort the market, are incredibly rare since sharp money usually dictates the lines. As bettors we are usually looking for odds where the oddsmaker has been pessimistic about the chance of an event occurring.

It is perhaps more practical to look for situations where bookmakers have miscalculated odds initially, and there is not the two-way money flow needed to correct the market.

Perhaps anchoring bias could ensure that bettors have not looked too deeply into the reasons behind this and the price has not yet been corrected. As Marco says, traders are not necessarily more informed than bettors – so finding isolated cases where markets have not been able to correct themselves could offer value.